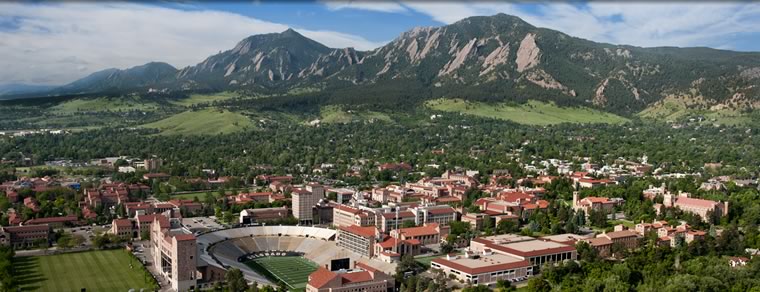

CU Boulder from above. (Will C Holden)

Opinions do not necessarily represent CUIndependent.com or any of its sponsors.

Disclosure: The author is currently a graduate part-time instructor, or GPTI, and will be teaching PHIL 2160 – Ethics and Information Technology – in Spring 2020.

On Sept. 23, 2019, I officially earned the University of Colorado Boulder’s Certificate in College Teaching. Earning this required 20 hours of workshops through the Graduate Teacher Program, 20 more hours of departmental training, two video consultations, one faculty observation and the creation of a teaching portfolio. CU really cares about training its teachers, right?

Right?

Unfortunately, that teacher training – which is less work than one regular semester-long course – is completely optional. If I just became “certified” in Fall 2019, what does that tell the hundreds of students I’ve taught since becoming a graduate part-time instructor, or GPTI, semesters ago? Here is the campus-wide required training for all those graduate students teaching your courses as GPTIs:

Unfortunately, that blank spot isn’t a formatting error. Despite the claims that CU Boulder cares about undergraduate education, there are no campus-wide requirements for training GPTIs on how to teach. There are more formal mechanisms in place to approve topics for these articles than there are to approve what I put on my syllabi. Given that GPTIs routinely teach many 1000 and 2000-level courses, CU’s commitment to your early education doesn’t look so good now, does it?

This isn’t an attack against GPTIs – far from it. Like most professors, instructors and staff, most GPTIs genuinely care about you. We are (often) early-career academics who are passionate about the academic material and about sharing that passion with our students. Many of us go out of our way to talk with faculty and fellow GPTIs to try to be the best instructors that we can be. But without university-mandated training or certifications, it’s hit-or-miss who you’ll have teaching your introductory classes.

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

A colleague in the education department recently told me about the apprenticeship-style training that he was required to do to teach at the K-12 level.

At the start, he would simply attend class to observe the teaching and have post-class discussions with the primary teacher. Eventually, he joined this experienced teacher in their lesson planning process. Slowly this apprentice was allowed to teach small segments of the class, while the experienced teacher gave them feedback after class. Eventually roles were swapped with the new teacher doing all the teaching, but still being observed and having required discussions with the experienced teacher after class. This took well over a year, on top of all the coursework on pedagogy and everything else he’d already gone through to learn how to be a quality teacher.

Perhaps we don’t need identical policies at the college level, but we can and should learn from the K-12 model. You don’t become less deserving of quality education once you enter college, do you?

Why not require that all future GPTIs take at least one semester of pedagogy classes? Why not require that they spend at least one semester apprenticing with experienced faculty, seeing how everything from syllabus creation to daily lesson planning to grading are handled by a trained professional? Why not require consistent observation by an experienced faculty, who can then discuss with the new teacher what went well and what didn’t, during at least their first semester?

“You don’t become less deserving of quality education once you enter college, do you?”

Maybe I’d know better if they trained me better, but I think I have the answer to why not: money. It would take a lot of money to implement policies aimed at making sure your teachers could teach, money that CU apparently would rather spend elsewhere.

But that money conversation is a long one, so you’ll have to tune in to part two later this week.

To be fair, none of this is unique to CU. It’s common for top research universities like ours to prioritize research over teaching. A quick look at US News shows that less than half of the top 20 schools for “Undergraduate Teaching” are also in the top 20 for “National Universities” overall. (If you’re curious, CU Boulder is number 104 for “National Universities” and we don’t seem to even have a rank for “Undergraduate Teaching.”) From discussions with faculty who earned their PhDs elsewhere and from looking at the optional Certificate in College Teaching through our Graduate Teacher Program, it seems like CU is actually doing relatively well. This doesn’t mean that CU doesn’t have drastic work to do to give you the consistently high-quality education you deserve, but rather is meant to show that we ought to rethink how higher education as a whole, at least at research universities, prioritizes undergraduate education.

The particular issue discussed here is about what CU does not do to make sure you get the quality education in your lower-level courses that you deserve. It’s also part of a larger issue, the issue of who has decision-making power. As I previously argued, we should be willing to radically rethink how decisions on this campus are made. If educating undergraduates is a major priority of institutes of higher education like CU, undergraduates should have a real seat at the table. Otherwise, your lower-level classes will continue to be hit-or-miss, depending on how motivated and how supported that particular GPTI happens to be.

The policies CU puts in place, and who CU allows to make such decisions, tells us a lot about what it values. By not mandating teacher-training for those who teach your introductory-level courses, CU is making one thing very clear: your education is not CU’s top priority.

Contact CU Independent Staff Writer Alex Wolf-Root at alexander.wolfroot@colorado.edu.