When I was a junior in high school, my football team ran the triple option offense. The triple is a run-based offensive scheme that has found success at the collegiate level at schools like Georgia Tech and Navy. During our homecoming game, we were faced with a 3rd and 21 scenario on our own 40 yard-line, if memory serves me correctly. We, along with everyone in the stands, figured we’d run a pass since we had one of the best wide receivers in the county on our team. Instead, our head coach called “21 triple-option,” which resulted in a gain of minimal yards. In a time where our team could’ve run a big play and changed the outcome of the game, the play call had us run what felt like the exact opposite thing, and we lost that game 21-14. Even though I was a junior and didn’t get much playing time, I walked into the locker room and lost my composure, and went home in a blind rage, disgusted with the play-calling that night.

While watching the Super Bowl on Sunday, the flashbacks were so vivid that I couldn’t help but make the comparison. With three downs left, forty seconds on the clock, and a timeout to burn, Seattle Seahawks head coach Pete Carroll and offensive coordinator Darrell Bevell thought it prudent to run a pass play in an attempt to punch it into the end zone.

Let’s just think about this for a moment.

The Seahawks faced Tom Brady, one of the top three quarterbacks in the last 15 years, if not top three quarterbacks of all-time, who torched the “Legion of Boom” in the fourth quarter of this game. In addition to Brady, Carroll also had to stare down kicker Stephen Gostowski, who had missed all of two field goals throughout the whole 2014 football season. Even if the Seahawks scored a touchdown on that play, it would’ve left the Patriots with roughly 35 seconds left on the clock to get within 45 yard field goal range, and let one of the best boots in the NFL go to work. What the Seahawks did have on their side was a timeout to burn and that same 35 seconds left on the clock, which made it perfectly possible to run three more plays to try and punch it in. Conceivably, you could knock 20 seconds off the clock, score a touchdown, give the Patriots 15 seconds left to work with and play a deep coverage zone, or “prevent,” with one of the best secondaries in the National Football League. Even with cornerback Richard Sherman and safety Kam Chancellor not at 100 percent and cornerback Jeremy Lane out of the game, it is a lot easier to defend in prevent with 15 seconds left than it is to hold 25 yards of field with 35 seconds left on the clock.

That’s the strategy of timing.

In addition to the time the Seahawks were afforded, Carroll also had running back Marshawn Lynch at his disposal, who is arguably the best power runner in the National Football League right now. The Patriots had to have multiple players on “Beast Mode” all night to try and take him down, and had limited success in goal-line situations. While Russell Wilson had played a solid game throughout the four quarters, it seems unconscionable to not use second down to run with Lynch, and then use third down to pass with Wilson. Is it predictable? Absolutely. But Seattle could’ve also ran a bootleg pass that would’ve pulled New England’s linebackers and secondary out of the box, allowing Wilson to either scramble or find an open receiver with more time. The other alternate sequence could also be to run the ball, and if you don’t make it, run a quick-snap to try and catch the Patriots defense in the middle of a formation change, and use the timeout on third down instead of second.

That’s the strategy of personnel.

Instead, Carroll and Bevell (while Carroll took responsibility for the call after the game, we may never know who had the final say) opted to have Wilson pass the ball on second down, looking to the inside on a slant when the Patriots were expecting a run and stacked the box. What happened was a Patriots interception, which resulted in a kneel-down, which resulted in a borderline brawl in the closing seconds.

The play-call set in motion a collection of moments that tainted the 49th Super Bowl. In a year when deflated footballs, domestic abuse, and DUI’s dominated the headlines, the final game of the season was supposed to be a final reminder of why we stay so attached to the league, even when we pledge to never watch it again. Thomas Davis’ Walter Payton man of the year acceptance speech the day prior to the Super Bowl was a PR dream for NFL executives, as it was a call to respond to the negative press by doing something that gave back to the community. I managed to get back into football, and sat with my eyes glued to the television through 45 minutes of a game at it’s highest level, enthralled with what was shaping up to be a great Super Bowl.

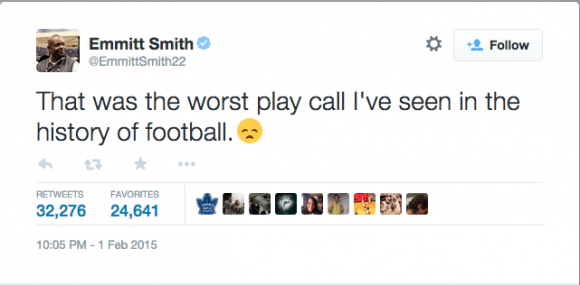

Instead, I left with the same sour taste in my mouth I had four months ago and all because of one call that was so out of left field that Hall of Fame running back Emmitt Smith called it “the worst play call in the history of football.” Don’t believe me? Well here is his tweet.

Instead of appreciating the brilliance of Tom Brady, the stoicism of Russell Wilson, or the unparalleled motor of Marshawn Lynch, we will spend the next week discussing the call and the absolute loss of composure by the Seahawks as the ball was being kneeled. As unfortunate as it may be, this Super Bowl sums up the 2014-2015 NFL season perfectly: moments of amazement that captivate us overshadowed by controversy that we can’t ignore.

As the years go by, we might be able to think about the greatness of this game: Pete Carroll’s gutsy pass play that led to a game-tying touchdown as halftime beckoned, or Tom Brady’s pocket presence that enabled him to find Julian Edelman nine different times, which resulted in 109 receiving yards and a touchdown.

But for now, we will think of the Super Bowl as a botched call and a brawl after the whistle, putting the cap on a captivating but controversial season. And that is just a shame.

Contact CU Independent Sports Editor Andrew Haubner at Andrew.Haubner@colorado.edu.